Dear friends,

We have entered the holiday season, and food insecurity becomes even harder for so many families during this time of the year. Our kids want to make a difference, and we need your help.

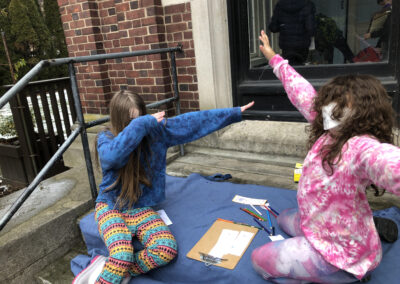

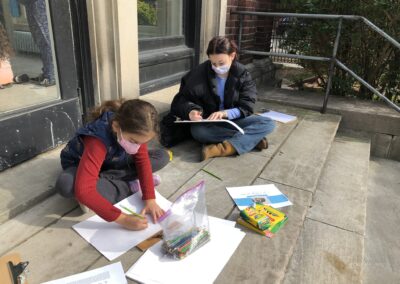

This month the kids from the Brooklyn Society for Ethical Culture ‘s Ethics for Children (

https://bsec.org/efc) service project wanted to stock the community fridge and pantry that is hosted by the Wyckoff Museum (5816 Clarendon Rd Brooklyn). Students will be assembling grab bag lunches for the fridge as well as collecting items ( new, not expired non-perishables as well as grab and go lunches for the community refrigerator) to stock the pantry.

If anyone would like to donate items, please feel free to drop them off with Taty this Friday, from 6-7pm at BSEC at 53 Prospect Park West, Brooklyn, NY), or Sunday, from 11:30am – 1:30pm with Angel at the BSEC Building Garden ( garden gate entrance on 2nd street, by Prospect Park West.

Thank you!

Our Ethics for Children student Westley Miller shared some exciting news this summer: His family is fostering a puppy! It has been really special hearing about his experience, so we asked him to share about it for our blog.

————

We are currently fostering a puppy. Fostering is kind of like adopting, except it is for a little bit, until someone

else wants it. The puppy’s name is Mae.

She was in the wild for a month while her siblings were in a shelter. There is a rescue in Dutchess County that

takes dogs from high-kill shelters in the south; it rescued Mae and her siblings, and we fostered Mae. All of

them had severe non-contagious mange.

Two days after being rescued from the shelter, one of her siblings died of dehydration and the other was

discovered to be a boy (the bad shelter thought they were all girls): Mae was doing better in the wild than her

siblings in the shelter. Her other sibling took longer to recover in his foster home than Mae did, and he is doing

great now and has been adopted. How did the “shelter” mistake him for a girl?

Mae has almost completely recovered from her mange (so has her brother), and I like having her in the house.

She is very annoying sometimes, but she is a very sweet puppy. She is nice to everything, she wants to play

with the cats and the goats, but the cats and goats don’t like her. Whenever anyone comes home, she is very

happy to see them, she wiggles around and jumps on them. We are trying to teach her not to jump on us.

Mae is doing very well with training, she does sometimes have accidents in the house when she gets excited,

Mae is doing very well with training, she does sometimes have accidents in the house when she gets excited,

but other than that she is doing well. Dad and I take her for walks.